- Home

- Willis E McNelly

The Dune Encyclopedia Page 8

The Dune Encyclopedia Read online

Page 8

They also took seeds for a growth called poverty grass, a mutated version of the plant which had been engineered by Salim, one of Kynes's first Fremen students. Tested in the Station facilities, the new grass had shown an encouraging ability to survive on only basic nutrients, airborne moisture, and a minimum of supplementary watering. In each of the dozen planting zones, it was planted along the downwind sides of old dunes, where it stabilized the sand against the prevailing westerly winds. This started a cycle: each stabilized area accumulated a higher windward crest after each sandstorm, which would in turn be planted with poverty grass, until sifs, barrier dunes of more than 1,500 meters' height were produced.

The work involved with the plantings was backbreaking, but moved quickly. In all but four of the test zones — in which the grass refused to take root — the barrier dunes were ready in a matter of months.

Kynes, in the meantime, had undertaken some new labors. After weeks of careful inquiry and widespread bribery, he had arranged for an interview with Altenes and Garik of Ix, the two men responsible for governing the Spacing Guild. Without explaining his reasons, but using the Guild's sensitivities concerning its melange supply, Kynes arranged that the Guild not permit observation satellites to be placed above the deep desert on Arrakis. The large amount of spice which the Guild demanded as payment was not permitted to weigh against the need for the planted areas, known as palmaries.

With the barriers in place, planting in the eight areas continued. Species from all over the Imperium were brought in and tried, beginning with chenopods, pigweeds, and amaranth. Tough, stringy, and difficult for even Arrakis to kill, this trio took only two years to provide bands of growth that were stable and, in the protection of the sifs, expanding outward.

This was the signal for slightly — but only slightly — more fragile plantings to be attempted. Scotch broom, low lupine, vine eucalyptus (originally adapted for the northern reaches of Caladan), dwarf tamarisk, and shore pine were placed at each site. The mortality rate of these newcomers was higher than that of their predecessors, in spite of the care the Fremen lavished on them, but those plants managing to survive were toughened by the trial and promised to produce strong seed.

Even such limited results were only obtainable at a tremendous expense of time and labor. Each plant was carefully tended, pruned, and cautiously watered; each was provided with its own dew collector to keep the additional moisture needed to a minimum. (Dew collectors were smooth chromoplastic ovals which were placed over the pit containing the plant's roots. During the day, the chromoplastic was gleaming white — at night, transparent. It cooled rapidly following the change, and condensed air moisture which then trickled down to the roots.) Aside from the work directly involved with the plantings, there was much support production needed: dew collectors, stillsuits, cloth, and all the other necessities for the sietch had to be manufactured.

Every member of the troop, at the earliest possible age, was expected to contribute. Fremen children, scarcely taller than the plants they policed, were taught to check dew collectors and remove dead or dying growths, and began instruction in the workings of Arrakis's ecology at age five.

Kynes's own son, known by his troop name of Liet, was no exception. Mitha, the boy's mother, died shortly after his birth in 10156, and Kynes allowed the child to be brought up among the other children of Sietch Tabr. Liet, along with his peers, divided his time between in-sietch education and work at the various plantings.

Kynes, knowing himself to be under more or less constant surveillance by the Harkonnens, stayed away from the palmaries. But his was still the guiding hand, and when the reports from his Fremen (in 10160) indicated that the second-stage plantings were now thriving, he ordered the process advanced.

Candellilla, saguaro, and bis-naga, or barrel cactus, were next in line, followed in 10163 by camel sage, onion grass, Gobi feather grass, wild alfalfa, burrow bush, sand verbena, evening primrose, incense bush, smoke tree, and creosote bush. Not all varieties took equally well at every site, but by 10167 each of the palmaries had more than tripled its original groundcover area, with increasingly large amounts of water being successfully tied into the root systems.

Animals were imported next: kit fox, kangaroo mouse, desert hare, and sand terrapin to burrow and keep the soil aerated; desert hawk, dwarf owl, eagle, and desert owl to keep the burrowers from overrunning the sites; scorpions, centipedes, trapdoor spider, biting wasp, and wormfly to fill other necessary ecological niches; and the desert bat, to keep the insects under control.

Finding the proper balances among the new arrivals took only two years — the ecologist-Fremen having learned their lessons well — and the palmaries were readied for their most crucial stage. More than 200 selected food plants, including coffee, date palms, melons, cotton, and various medicinals, were smuggled in from offplanet and dispersed among the palmaries.

Knowing how vital to their goal the survival of these plants was, the Fremen worked harder than ever. In some cases, round-the-clock watches were set up over newly planted areas to ensure their safety from raids by the nocturnal rodents. Whenever a plant failed, the remains were as carefully examined as an autopsied emperor.

Information was routed back to Kynes, chiefly through his son, who had become a sandrider at the usual age of twelve. Liet's powers of memory and observation were good, and over the next three years he carried increasingly encouraging reports to his father. Of the varieties planted, over a hundred had been successfully cultivated without major change. Of those which remained, seventy-five had been discovered to be adaptable to Arrakis, through grafting, crossbreeding, or alteration of seeds by various external stimuli. (The Fremen Salim, beyond doubt Kynes's star pupil, had assembled a group specializing in this type of treatment.) Only thirty-odd plants proved absolutely incapable of surviving.

As the cultivated areas expanded farther, however, a strange phenomenon was noticed. Protein incompatibility was poisoning the sand plankton which came in contact with the new lifeforms. At the desert edge of each palmary, a barren zone was formed, saturated with poisonous water which none of the Arrakis life would touch.

This was an unforeseen development, and one which Kynes did not feel competent to handle on other than an on-the-spot basis. Fabricating a story about an obscure type of plant he wished to investigate at an outlying sietch, the planetologist managed to elude the Harkonnens and arrange transportation to the south. (He made the twenty-thumper trip in a palanquin, carried by his Fremen, as though he were a wounded man or Reverend Mother, since he had never become a sand-rider.)

For three days after his arrival at the barren zone, Kynes locked himself into his yali, his personal quarters where no other would dare disturb him, and examined samples of the poisoned soil. On the morning of the fourth day, looking as haggard as a man who had walked in from the Great Flat, he emerged, and delivered electrifying news to the anxious Fremen.

The poison was a disguised blessing, a gift from Shai-Hulud! The addition of fixed nitrogen and sulfur to the chemicals produced by the decomposed sand plankton would convert the barren zone to rich soil in which their plantings could thrive. The speed with which the palmaries could expand would now be determined solely by the amount of labor the Fremen could afford them, and by the volume of water available.

The new advance cut down Kynes's projected timetable for the transformation considerably — to a mere three and one-half centuries. But the Fremen were a people who had learned patience at the hands of men with whips; they were content to wait, knowing that their labors would buy glory for themselves and a living paradise for their descendants.

The palmaries continued on the course Kynes had set, tenderly cared for by the Fremen and unknown to any outsiders for almost half a century. Kynes's death in 10175, in a cave-in at Plaster Basin, caused no deviation from the plan. Nor did the Harkonnen-Atreides warfare, the demise of Liet-Kynes (who had inherited his father's place with the tribes) in 10191, nor even the ascension of Paul Muad'D

ib Atreides in 10196. When the soldiers of the Jihad left Arrakis it was with the knowledge that those left behind were also fighting for their cause by tending the palmaries.

Not until 10221, when Leto II allowed himself to be transformed into the superhuman being who would rule for over three thousand years, was Pardot Kynes's plan brooked. As wise and as farsighted as the planetologist had been, he had never imagined that his timetable might conflict with that of a god.

Leto II, just beginning his reign, needed time. He knew that he would continue, and perhaps hasten, the transformation which Kynes had initiated, but he had not yet decided at what pace it would be done. In 10221 he purchased a breathing space of several decades by destroying the qanats of four of the eight palmaries: Gara Rulen, Windsack, Old Gap, and Harg2.

Deprived of their water, the still-fragile plantings withered and died. This left only half the original number of green areas — Wind Pass, Chin Rock, Hagga Basin, and Tsimpe — to harbor Kynes's, and his Fremens', dreams.

The Fremen, terrified by the sudden destruction, but unable to face abandoning their work, concentrated their efforts on the remaining sites and hoped for peace.

Leto II, once his rule was firmly established, gave them rather more than that. He brought the decades-old secret into the open, acknowledged the palmaries' existence, and made their advancement an Imperial priority. The Fremen were able to go on with their work at a pace which would have astonished and gratified Pardot Kynes.

By 10260, fifty palmaries, each larger than any of the original sites, Were in various stages of completion; a century later, they had spread over enough of the Arrakis surface to establish the "self-sustaining cycle" which Kynes had originally predicted would occur. (He had estimated that three percent of the green plant element would have to be involved in forming carbon compounds to start the cycle working, and he was very nearly correct. The actual figure was 3.92 percent.)

As the greenbelts and groves took over larger and larger segments of the planet, the native lifeforms, including the sandworms, were driven off into increasingly smaller reservations. The establishment of Kynes's cycle signaled the end for them: the last sandworm sighting occurred in 10402, and the sandworm was in its death throes.

The God Emperor stepped in once again, ordering the placement of Ixian weather-control satellites over the small area of the planet which remained desert. While weather satellites had been in use on Arrakis to one degree or another since the rule of Leto II's father, these were intended for a use unique in the planet's history. Earlier satellites had been brought in to help gentle the fierce climate; these were intended to bring back some of that lost ferocity, to preserve one small piece of Arrakis, the Sareer, in as close to its original form as possible.

The work for which the palmaries had been designed was completed, well ahead of the fondest expectations of the man who had first evisioned them. Arrakis, Dune, the Desert Planet, in a sense existed no longer.

C.T.

NOTES

1In 10148, Cartha fungus threatened to destroy Ecaz's entire fogwood crop; Kynes recommended importing spores of Kuenn's Fungus, a benign growth which crowded out the Cartha, saving the valuable wood.

2The eight palmaries were named for eight of the Imperial Testing Stations; in this way, it was hoped, they could be mentioned without alerting the Harkonnens.

Further references: ARRAKIS, ATMOSPHERE OF BEFORE THE ATREIDES; Pardot Kynes, Ecology of Dune, tr. Ewan Gwatan, Arrakis Studies 24 (Grumman: United Worlds); Harq al-Ada, The Story of Liet-Kynes (Work-in-Progress, Arrakis Studies, Temp. Ser. 109, Lib. Conf.).

ARRAKIS, Geology

(A multitude of papers have appeared during the last several thousand years discussing the origin, evolution, and present state of planets and planetary systems. The geologic history of Arrakis is fascinating, but no more so than of a great number of other planets. No good or recent review of its geology exists. The information presented here is culled from many published reports, too numerous to list. The only references given are to those papers which contain information of special interest.)

GEOMETRIC ASPECTS. Arrakis revolves about Canopus at a mean distance of 87 million kilometers, significantly closer than most C subclass planets, C designating third major from the primary. The planet's orbit about Canopus was roughly circular about 5,000 years ago. However, the second (B) and fourth (D) planets circling Canopus, neither habitable, are much larger than Arrakis. The inner, Menaris, has a mean equatorial radius of 7,862 kilometers while the outer, Extaris, has a radius of 8,112 kilometers. Arrakis by comparison has a corresponding radius of only 6,128 kilometers (actually 6127.9621438 kilometers as of year 14521 for those readers interested in such details). Menaris and Extaris also have highly elliptical orbits lying well outside the ecliptic plane defined by the orbit of Arrakis about Canopus. As a result of the gravitational pulls of these planets, informally called "the Twins," Arrakis is now known to achieve a highly eccentric orbit, maximum ellipticity 2.1, every 12,323 years. The Twins also have a profound impact upon Arrakeen geology and tectonics.

The length of the year varies from 295 standard days to 595. At present it is 353 days. When Arrakis is in its most elliptical phaseseasonal changes are extreme. Winters are extremely severe all over the planet. Throughout historical times, the orbit has been roughly circular, for the most part, with very little in the way of seasonal change. Only the geological record and theoretical calculations tell us that conditions during the past were drastically different from those we now experience.

Arrakis has two natural moons. A third was destroyed by impact from an on-rushing asteroid/comet. A ring structure was formed, circling the planet, but most of the debris impacted the planet's surface. Since the moon lay in Arrakis's ecliptic plane, the ring of dust caused a major reduction in star energy striking the surface. Hence surface temperatures were reduced and an ice age occurred. Many life species perished while others assumed dominance. Many believe that oft-told legends refer to this event, and would place it at about 35,000 years before the present. But geological data suggest that the event occurred at least 200,000 years ago.

The two remaining moons cause major changes in Arrakis's rotation about its own axis. The Twins also contribute, but their effects are long-term. Arrakis averages 22.4 standard hours per day. However, the shortest days of record occurred from 12310 to 12420 with the absolute shortest day being 5.28 hours in duration. This occurred on 5 nElroodim 12370 Imperial. The longest day recorded thus far was 43.2 standard hours (25 nAlraanim 15052 Imperial). Theoretical calculations show that under special circumstances the day can be as short as 3.81572 hours and as long as 51.36405 hours. These changes in rotation rate, as well as the effects of Menaris and Extaris have had profound impact on the geologic evolution of Arrakis.

MORPHOLOGY. The first complete mapping and interpretation of the surface of Arrakis was done by Kynes (10901), who claimed to be an eighth generation descendant of the famous planetologist of the same name who lived during the time of Paul Muad'Dib. Dramatic changes have occurred since then and these changes as well as present topography are detailed by Xenach (15029). At present many mountain ranges and deep valleys (grabens) exist in all regions of the planet, a situation similar to that of the earliest known phase of the planet's history. During the middle phase, as existed during Kynes's time, extensive desertification had occurred. The earlier mountains had been severely eroded, primarily by sand blasting, and the surface was mostly flat except for isolated garres and ridges, a few volcanic peaks such as Mt. Idaho, Mt. Kynes, and Observatory Mt., and the dune fields.

It is only because the planet is so geologically active that any elevation difference, other than the sand dunes, existed at all during the middle phase. Arrakis is the most geologically active of all Neta planets and the rate of mountain building almost managed to keep pace with rapid erosion by sand blasting. Today with much-reduced eolian erosion as a result of the greening of Arrakis, and with little in the way of water erosion,

mountains are rising rapidly (rapidly in a geological time sense). Mt. Idaho is still the highest peak. Its summit is currently 9,524 meters above the bled, compared to only 7,393 meters seven thousand years ago. Several mountain ranges now have peaks exceeding 7,400 meters in elevation.

There are numerous deep valleys (grabens), the greatest of which is Grose Valen, with maximum depth of 1,250 meters, maximum width of 2,800 meters and a length of about 730 km. During the desertification phase of the planet's history, most of these were filled with dust and called tidal dust basins or dust chasms by the natives. Today many of these chasms have reopened through geological processes, and many more have formed. The major grabens are not formed by running water; rather they are a result of the dynamic development of the planet, discussed in the next section. Filling of the chasms today results primarily from landslides and rockfalls. The chasms provide much more of an obstacle to surface travel than the mountain ranges since they can be crossed only by very long and expensive bridges, and they expand and contract so rapidly that no bridge lasts very long. Hence most travel is by air.

Few permanent rivers or bodies of standing water are present on Arrakis and drainage systems are poorly developed even after the ecological transformation completed by Leto II. Flash floods occur occasionally in mountainous areas, but all in all Arrakis is still quite water poor. Water ice is present in the polar caps, as is the case with all Neta-2C planets, but the total amount is small compared to that of other planets of the group. Garres are plentiful, and are easily distinguished by their flat tops. They are the oldest exposed areas on the planet, being remains of ancient plateaus formed by widespread lava flow very early in the planet's evolution when water was plentiful and water erosion dominant. Ancient water courses are still visible on their tops and their sides.

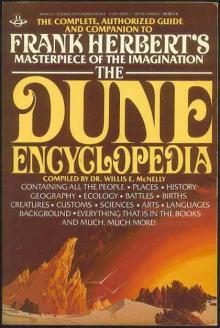

The Dune Encyclopedia

The Dune Encyclopedia